The nervous system comprises the brain, spinal cord and the network of nerves that transmits signals to and from different parts of the body, to coordinate action and sensory inputs. It is highly complex and subject to biochemical imbalances and structural changes that manifest as neurological diseases.

This module focuses on the drug classes that are the most effective treatments for common neurological conditions. In many situations the main objective of current therapies is to reduce debilitating disease symptoms rather than provide a cure.

If you have relevant content you are willing to share, we would appreciate your contribution. Contact admin@pharmacologyeducation.org, or complete the webform on the Contribute to the Project page.

5-HT1 receptor agonists

The 5-HT1A receptor is a serotonin receptor subtype found in presynaptic and postsynaptic regions of the brain that is implicated in the control of mood, cognition and memory.

The role of 5-HT in anxiety is well established. Of note, buspirone, originally thought to achieve its anxiolytic effects solely through antagonism of D2 receptors, was subsequently discovered to be an agonist of 5-HT1A receptors. It is now aknowledged that buspirone acts as a full agonist at presynaptic 5-HT1A receptors and as a partial agonist at postsynaptic receptors in the hippocampus and cortex. The role of 5-HT1A receptors in depression has also been demonstrated, indeed antidepressants such as MAOIs and TCAs, SSRIs, lithium and valproate are known to directly or indirectly increase postsynaptic 5-HT1A signalling, an action which may play a role in their antidepressant effect. In particular, research has shown that vilazodone may exert its antidepressant effect through the combined effect of serotonin reuptake inhibition and partial agonism of 5-HT1A receptors. Research also suggests that compounds possessing balanced 5-HT1A receptor agonism and D2 antagonism are effective antipsychotics, and might achieve the desired therapeutic benefit by targeting the receptors responsible for the beneficial drug effect but avoid modulation of receptors that are responsible for side-effects.

As can be seen, activation of 5-HT1A receptors contributes to the clinical effects of many anxiolytic, antidepressant and antipsychotic medications. In the future, ‘biased agonists’ (functionally selective agonists which optimise therapeutic benefit) may prove to be a novel solution for managing psychiatric disorders that are associated with 5-HT1A receptors.

Clinically relevant 5-HT1A partial agonists include the antianxiety agent, buspirone, the second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics, clozapine, ziprasidone, aripiprazole and brexpiprazole, and the antidepressant vilazodone.

Anti-emetic drugs

Drug-induced emesis can now be largely controlled with anti-emetic drugs, however, nausea remains a very significant clinical problem. This dichotomy suggests that different mechanisms underlie nausea and vomiting.

Major classes of anti-emetic drugs:

5-HT3 receptor antagonists– ‘setrons’ e.g. ondansetron and palonosetron which are used to suppress chemotherapy- and radiation-induced emesis and post-operative nausea and vomiting. These drugs are not effective against motion sickness, or vomiting induced by agents increasing dopaminergic transmission. Drug action can be improved by co-administration of a corticosteroid or neurokinin 1 (NK1) receptor antagonist (see below).

Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor antagonists– e.g. hyosine (scopolamine), used for prophylaxis and treatment of motion sickness. Many side-effects including sedation and parasympathimimetic action (blurred vision, urinary retention, dry mouth).

Histamine H1 receptor antagonists– e.g. cyclizine, cinnarizine and many others, used for prophylaxis and treatment of motion sickness, vertigo and acute labyrinthitis and nausea and vomiting caused by irritants in the stomach. Concomittant antagonism of muscarinic receptors by these agents likely contributes to their activity. Side-effects include CNS depression and sedation.

Dopamine receptor antagonists– e.g. domperidone and metoclopramide, used to treat drug-induced vomiting and vomiting in gastrointestinal disorders. Phenothiazines (antipsychotics, e.g. chlorpromazine and prochlorperazine) which owe part of their action to dopamine D2 receptor antagonism are used for severe nausea and vomiting.

NK1 receptor antagonists– e.g. aprepitant, its prodrug fosaprepitant, and netupitant, used in combination with a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone in the acute phase of highly emetogenic chemotherapy.

Cannabinoid (CB1) receptor agonists– e.g. nabilone, used for treatment of nausea and vomiting caused by cytotoxic chemotherapy that is unresponsive to other anti-emetics. May cause dizziness and drowsiness, impairing physical or mental abilities. Can also cause tachycardia and/or orthostatic hypotension, so caution is advised if prescribing to patients with cardiovascular disease.

RESOURCES

Anti-epileptic drugs

These 40 slides focus on the drugs used to treat epilepsy (anti-epileptic drugs). The anti-epileptic drugs presented are classified according to their main molecular mechanism of action. Additionally, there is information presented for the indication for epilepsy type, principal side effects and a brief summary of the pharmacokinetics of the anti-epileptic drugs. These slides are intended for pharmacology, medical and/or pharmacy students at an intermediate level. Produced for the PEP by Stephen Kelley (University of Dundee, UK).

Anticonvulsants drugs

Anticonvulsants drugs can be classified according to their molecular mechanism of action. In general, the most useful mechanisms exploited therapeutically are those that enhance gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) action and inhibit sodium channel activity. Other mechanisms include inhibition of calcium channels and glutamate receptors.

AMPA receptor antagonists: Perampanel (the first and only FDA-approved non-competitive AMPA receptor antagonist) is used as an adjunctive therapy in the treatment of focal seizures with or without secondary generalised seizures.

Barbiturate anticonvulsants: Barbiturates act as positive allosteric modulators of GABAA receptors (or GABA receptor agonists at high doses) and block the excitatory AMPA and kainite glutamate receptors. These drugs bind to receptor site discinct from the GABA and benzodiazepine binding sites. Barbiturate action elevates seizure threshold and reduces the spread of seizure activity from a seizure focus. Primidone is indicated for the treatment of all forms of epilepsy except typical absence (petit mal) seizures and essential tremor. Phenobarbital is indicated for the treatment of all forms of epilepsy except typical absence seizures and status epilepticus.

Benzodiazepine anticonvulsants: Diazepam can be used to control muscle spasms of varied aetiology, status epilepticus, febrile convulsions, convulsions due to poisoning, and acute drug-induced dystonic reactions. Clonazepam can be used to treat all forms of epilepsy and myoclonus. Lorazepam can be used alongside other medications to treat seizures, for example slow intravenous injection is used in the control of status epilepticus, febrile convulsions and poison-induced convulsions.

Carbamate anticonvulsants: Felbamate (not available in the UK) appears to exhibit some inhibitory effect at N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor and to modestly potentiate GABA activity. It has broad spectrum anti-epileptic activity but due to its propensity to cause severe side-effects (e.g. aplastic anemia, hepatitis and liver failure) it is generally only used in patients who are unresponsive to other anticonvulsant drugs.

Carbonic anhydrase inhibitor anticonvulsants inhibit the enzyme carbonic anhydrase. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors have several clinical uses, including treatment of epilepsy, glaucoma, mountain sickness, and as diuretics. Topiramate appears to enhance GABA action via effects on kainate and AMPA receptors to bring about inhibition of the excitatory neurotransmission underlying seizure generation. Topiramate can be used as monotherapy or adjunctively to treat generalised tonic-clonic seizures or focal seizures with or without secondary generalisation and as an adjunctive treatment for seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome.

Dibenzazepine anticonvulsants: Oxcarbazepine is approved for use as monotherapy or adjunctive treatment for focal seizures with or without secondary generalised tonic-clonic seizures and treatment of primary generalised tonic-clonic seizures. Eslicarbazepine acetate can be used as an adjunctive treatment in adults with focal seizures with or without secondary generalisation.

Fatty acid derivative anticonvulsants appear to increase the availability of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA. They have several mechanisms of action. They have inhibitory action against GABA transaminase, which breaks down GABA. This leads to increased concentration of GABA in the synapses. Other proposed mechanisms of action that account for their anticonvulsant properties is they either enhance the action of GABA or mimic its action at postsynaptic receptor sites. They also block voltage gated sodium channels and T-type calcium channels, and cause inhibitory activity in the brain. Fatty acid derivatives are broad-spectrum anticonvulsant drugs, which are effective against most types of seizures, including absence seizures, tonic-clonic seizures, juvenile myoclonic epilepsy and complex partial seizures. Valproic acid and sodium valproate (1:1 dose-equivalency) are used to treat generalised, partial or other forms of epilepsy.

Gamma-aminobutyric acid analogs generally act as GABA receptor agonists and cause inhibitory action just like endogenous GABA, although gabapentin’s ability to bind GABA receptors is debated. Gabapentin can be used as monotherapy or adjunctive treatment for focal seizures with or without secondary generalisation. Pregabalin can be used as adjunctive therapy for focal seizures with or without secondary generalisation. Vigabatrin can be used as an adjunctive treatment for focal seizures with or without secondary generalisation not satisfactorily controlled with other anti-epileptics (under expert supervision).

Gamma-aminobutyric acid reuptake inhibitors are analogues of GABA that bind to GABA transporters and inhibit GABA reuptake. This increases extracellular levels of GABA and enhances GABA mediated synaptic activity in the brain. Tiagabine may be used as adjunctive treatment for focal seizures with or without secondary generalisation that are not satisfactorily controlled by other anti-epileptics, with or without enzyme-inducing drugs.

Hydantoin anticonvulsants are structurally related to barbiturates. They have an allantoin heterocyclic base. They act to slow synaptic transmission by blocking sodium channels from recovering from the inactivated state, and inhibit neuronal firing. This inhibits the repeated excitation of cells that results in seizures. Hydantoin anticonvulsants are used to treat a wide range of seizures types. Phenytoin can be used to manage tonic-clonic seizures, focal seizures and for acute symptomatic therapy, prevention and treatment of seizures during or following neurosurgery or severe head injury, and for status epilepticus. Preparations containing phenytoin sodium are not bioequivalent to those containing phenytoin base (100 mg of phenytoin sodium is approximately equivalent in therapeutic effect to 92 mg phenytoin base). Fosphenytoin sodium is used in the management of status epilepticus, as prophylaxis or treatment of seizures associated with neurosurgery or head injury (dose-equivalence: 1.5mg fosphenytoin sodium ≡ 1mg phenytoin sodium). Ethotoin (not available in the UK) is used to treat generalized tonic-clonic or complex-partial seizures.

Miscellaneous anticonvulsants: Magnesium sulfate may be used in the prevention of seizures in pre-eclampsia and treatment of seizures and prevention of seizure recurrence in eclampsia. Lacosamide is used as adjunctive therapy of focal seizures with or without secondary generalisation. Rufinamide (a triazole derivative sodium channel inactivator) can be used as an adjunctive treatment for seizures in Lennox-Gastaut syndrome with valproate.

Neuronal potassium channel openers: The only such drug, retigabine (a.k.a. ezogabine), binds the KCNQ (Kv7.2-7.5) voltage-gated potassium channels, which stabilises the channels in the open formation and enhances the M-current. This action controls neuronal excitability such that epileptiform activity is suppressed. Retigabine may also augment GABA-mediated currents. Retigabine is used as adjunctive treatment of drug-resistant focal seizures with or without secondary generalisation when other appropriate drug combinations have proved inadequate or have not been tolerated.

Oxazolidinedione anticonvulsants are used to treat absence seizures. The exact mechanism of action of oxazolidinedione anticonvulsants is unknown. An example is trimethadione (not available in the UK) which is used to treat absence seizures in adults and children where other anti-epileptics have been unsuccessful.

Pyrrolidine anticonvulsants are used as anti-epileptics, although the exact mechanism of action is not fully defined. They appear to depress nerve transmission. Levetiracetam is used as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy for focal seizures with or without secondary generalisation and as adjunctive therapy of myoclonic seizures and tonic-clonic seizures.

Succinimide anticonvulsants are thought to increase the seizure threshold, inhibit T-type calcium channels and inhibit the three-cycle per second thalamic ‘spike and wave’ discharge in absence seizures. They also appear to depress nerve transmission in the motor cortex. Ethosuximide is used to treat absence seizures, atypical absence seizures (adjunct) and myoclonic seizures. Methsuximide (not available in the UK) is used to control of absence seizures that are refractory to other drugs.

Triazine anticonvulsants act on presynaptic sodium channels which subsequently inhibits release of the excitatory neurotransmitters, glutamate and aspartate. Lamotrigine can be used as monotherapy of focal seizures, primary and secondary generalised tonic-clonic seizures and seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and as adjunctive therapy of these three indications with valproate.

Antidepressant drugs

In patients with moderate to severe depression routine antidepressant therapy is effective (as highlighted by Cipriani et al. (2018) following meta-analysis of results from clinical trials of 21 different antidepressants)- and is recommended to be combined with psychological therapy. Drug treatment of mild depression may also be considered in patients with a history of moderate or severe depression. Improvement in sleep is usually the first benefit of antidepressant therapy, with additional beneficial effects on psychomotor and physiological changes such as loss of appetite. The information provided in this section summarises the classes of antidepressants available to the prescriber. For a more critical review of antidepressant therapy see our topic Depression within in the Psychiatric disease module.

The major classes of antidepressant drugs include the tricyclic and related antidepressants, selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs), the selective serotonin and norepinephrine re-uptake inhibitors (SNRIs) and the monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). A small number of drugs don’t easily fall into this classification and are listed under Atypical antidepressants below.

There is little to choose between the different classes of antidepressant drugs in terms of efficacy, so choice should be based on the individual patient’s requirements, including the presence of other existing disease and therapy, suicide risk, and previous response to antidepressant therapy.

SSRIs are better tolerated and are safer in overdose than other classes of antidepressants and should be considered first-line for treating depression. Notably, sertraline has been shown to be safe in patients who have had a recent myocardial infarction or who have unstable angina. TCAs have similar efficacy to SSRIs, but their more troublesome side-effects leads to patients being more likely to discontinue treatment. TCAs are also more toxic in overdose than SSRIs. MAOIs have dangerous interactions with some foods and drugs, and should be reserved for use by specialists.

Anxiolytics or antipsychotic drugs should be used with caution in depression which often presents as anxiety, as they can mask the true diagnosis, but are useful adjuncts in agitated patients.

Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

SSRIs are the most commonly prescribed class of antidepressants. They are highly effective and generally well tolerated compared to other types of antidepressants. Side effects of SSRIs may include nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, sexual dysfunction, headache, weight gain, anxiety, dizziness, dry mouth, and insomnia. Caution should be used when prescribing SSRIs alongside other drugs that increase the risk of bleeding. SSRIs should not be used in patients with poorly controlled epilepsy or in patients entering manic phase. Common shared side-effects (often dose-related) include abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhoea, dyspepsia, nausea and vomiting. An uncommon, but potentially serious side-effect is serotonin syndrome.

Citalopram– used to manage depressive illness and panic disorder.

Escitalopram (the active enantiomer of citalopram)- used to manage depressive illness, generalised anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder and social anxiety disorder.

Paroxetine– used to manage major depression, social anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), generalised anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder and panic disorder

Fluoxetine (Prozac)- used to treat major depression, bulimia nervosa and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Prescribers should consider the long half-life of when adjusting dosage, especially in regards to overdosage.

Fluvoxamine– used to manage depressive illness and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Sertraline– used to manage depressive illness, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder and PTSD.

Failure to respond to initial treatment with an SSRI may require an increase in the dose, or switching to a different SSRI or mirtazapine. Other second-line choices include lofepramine, moclobemide, and reboxetine.

Selective serotonin and norepinephrine re-uptake inhibitors (SNRIs)

None of these drugs should be prescribed within 14 days of an MAOI and at least 7 days should be allowed between stopping their use and administering a MAOI.

Desvenlafaxine (not UK)- indicated for major depressive disorder.

Duloxetine– used to manage major depressive disorder, generalised anxiety disorder, diabetic neuropathy and moderate to severe stress urinary incontinence. Use caution when prescribing alongside drugs that increase risk of bleeding.

Venlafaxine– indicated for major depression, generalised anxiety disorder and social anxiety disorder. Contra-indicated in patients with conditions associated with high risk of cardiac arrhythmia or uncontrolled hypertension.

Milnacipran (not UK)- used to treat the chronic pain caused by fibromyalgia, not used to treat depression.

Levomilnacipran (not UK)- used to treat major depressive disorder.

Most common side-effects of SNRIs are nausea, dizziness, and sweating. Other side-effects include tiredness, constipation, insomnia, anxiety, headache, and loss of appetite.

Duloxetine and milnacipran should not be used in patients with uncontrolled narrow angle or angle-closure glaucoma.

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and related antidepressants

TCAs share a similar chemical structure and biological effects. TCAs block the re-uptake of both serotonin and noradrenaline, although to different extents. For example, clomipramine is more selective for serotonin re-uptake, and reboxetine and lofepramine are somewhat more selective for noradrenaline re-uptake. Other TCAs such as nortriptyline, show no such selectivity. Evidence indicates that the secondary amine tricyclic antidepressants, including desipramine HCl, may have greater activity in blocking the re-uptake of norepinephrine. Tertiary amine tricyclic antidepressants, such as amitriptyline, may have greater effect on serotonin re-uptake. Additionally, TCAs block muscarinic M1, histamine H1, and alpha-adrenoceptors. Tricyclic and related antidepressant drugs can be roughly divided into those with additional sedative properties (amitriptyline, clomipramine, dosulepin, doxepin, mianserin, trazodone, and trimipramine) and those that are less sedating (imipramine, lofepramine, and nortriptyline). Agitated and anxious patients tend to respond best to the sedative compounds, whereas withdrawn and apathetic patients will often obtain most benefit from the less sedating ones.

TCAs are approved for treating several types of depression, obsessive compulsive disorder, and bedwetting (nocturnal enuresis). Also used for several off-label conditions such as panic disorder, bulimia, chronic pain (for example, migraine, tension headaches, diabetic neuropathy, and post herpetic neuralgia), phantom limb pain, chronic itching, and premenstrual symptoms

Although effective, TCAs have largely been replaced by newer antidepressants that generally cause fewer side-effects.

Amitriptyline – not recommended for depressive illness because of its toxicity in overdosage- used for migraine prophylaxis, neuropathic pain, abdominal pain or discomfort (in patients who have not responded to laxatives, loperamide, or antispasmodics)

Doxepin– used for depressive illness (especially where sedation is required) and pruritus of eczema (topical application). This TCA acts as a selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor. Dizziness and drowsiness are very common side-effects, as are agitation, anxiety, confusion, irritability, paraesthesia and sleep disturbance.

Lofepramine– used to treat depressive illness. Common side-effects include dizziness, agitation, anxiety, confusion, irritability, paraesthesia, postural hypotension and sleep disturbance

Dosulepin hydrochloride- used for depressive illness (especially where sedation is required). Common side-effects include dizziness, agitation, anxiety, confusion, irritability, paraesthesia, postural hypotension and sleep disturbance

Desipramine hydrochloride (not UK), is approved in the US to treat symptoms of depression. Use of desipramine in patients being treated with MAOI antidepressants (e.g. linezolid) is contraindicated because of an increased risk of serotonin syndrome. Desipramine may cause exacerbation of psychosis in schizophrenic patients. Concomitant use of tricyclic antidepressants with drugs that can inhibit cytochrome P450 2D6 may require lower doses than usually prescribed for either the tricyclic antidepressant or the other drug.

Imipramine hydrochloride – used for depressive illness and nocturnal enuresis. Common side-effects include fatigue, flushing, headache, palpitations and restlessness.

Nortriptyline – prescribed for depressive illness and neuropathic pain. Treatment should be stopped if the patient enters a manic phase. Common side-effects include fatigue, hypertension, mydriasis and restlessness

Amoxapine (not UK)- used to treat symptoms of depression, anxiety, or agitation. Do not use this medicine within 14 days of taking an MAOI antidepressant.

Clomipramine hydrochloride- prescribed for depressive illness, phobic and obsessional states and as an adjunctive treatment of cataplexy associated with narcolepsy. Common side-effects include abdominal pain, aggression, diarrhoea, fatigue, flushing, hypertension, impaired memory, muscle hypertonia, muscle weakness, mydriasis, myoclonus, restlessness and yawning.

Maprotiline (not UK)- used to treat major depressive disorder, depressive neurosis, and manic-depression illness. Avoid alcohol as it can increase some of the side-effects of maprotiline. Maprotiline can impair thinking or reactions, so patients are recommended to avoid activities that require alertness (e.g. driving)

Trimipramine– used to treat depressive illness (particularly where sedation is required). Side-effects can include agitation, anorexia, anxiety, arrhythmia, blurred vision, confusion, constipation, dizziness and dry mouth. Trimipramine is also a serotonin 5-HT2 receptor antagonist.

Protriptyline (not UK)- used to treat symptoms of depression. Do not use this medicine within 14 days of taking an MAOI antidepressant. Common side-effects can include nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, anxiety, insomnia, dry mouth, little or no urinating and constipation.

Monoamine oxidase inhibitor antidepressants (MAOIs)

MAOIs block the activity of monoamine oxidase, an enzyme that breaks down norepinephrine, serotonin, and dopamine in the brain and other parts of the body. MAOIs are used much less frequently than tricyclic and related antidepressants, or SSRIs and related antidepressants because of the dangers of dietary and drug interactions. MAOIs exhibit some benefit for phobic patients and depressed patients with atypical, hypochondriacal, or hysterical features, but should only be prescribed by specialists. In general, MAOIs have been replaced by newer antidepressants that are safer and cause fewer side-effects. Common side-effects include postural hypotension, weight gain, and sexual side effects.

Isocarboxazid, phenelzine and tranylcypromine are non-selective, irreversible MAOIs, used to manage depressive illness.

Rasagiline and selegiline are irreversible MAOB inhibitors used not to treat depression, but to treat Parkinson’s disease as a monotherapy or as an adjunct to co-beneldopa or co-careldopa to manage ‘end-of-dose’ fluctuations.

Atypical antidepressants

Each drug in this category has a unique molecular mechanism of action, or a chemical structure that excludes them from the classification above. However, like other antidepressants, atypical antidepressants affect the levels or effects of dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine in the brain.

Bupropion– used to aid smoking cessation in combination with motivational support in nicotine-dependent patients. This drug should not be used in patients with seizure disorders, eating disorders, and within 2 weeks of using MAOI. It generally does not cause weight gain or sexual problems.

Mirtazapine– a presynaptic α2-adrenoceptor and serotonin 5-HT2 receptor antagonist which increases central noradrenergic and serotonergic neurotransmission. Used to manage major depression.

Nefazodone (not UK)- a serotonin 5-HT2 receptor antagonist also inhibiting serotonin and norepinephrine re-uptake. Used to manage depression, including major depressive disorder. Nefazodone should not be prescribed to patients with active liver disease.

Trazodone– principally a serotonin 5-HT2 receptor antagonist, used to manage depressive illness, particularly where sedation is required.

Vilazodone (not UK)- a potent serotonin 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist, with combined inhibitory action against serotonin re-uptake. Used to manage major depressive disorder. Vilazodone is not associated with significant weight gain or sexual dysfunction.

Vortioxetine (not UK)- a partial agonist of 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptors and antagonist of the 5-HT7 receptor used to manage major depressive disorder. May also inhibit re-uptake of serotonin.

Side-effect profiles are as unique as their mechanisms of action. Some common side effects include dry mouth, constipation, dizziness, and light headedness. Mirtazapine and trazodone cause drowsiness and are usually taken at bedtime

Note: The drug lists presented here are not exhaustive, but are intended to represent the majority of antidepressants in use in the UK and US. Additional drugs may be approved in other countries.

RESOURCES

This 13-slide slide set created with PowerPoint provides an introduction to antidepressants describing their discovery and development; their modes of action and relationship to the monoamine hypothesis of depression; and their efficacy, latency and unwanted actions. The beginner level introduction is tailored to aid the understanding of individual antidepressants. Contributed by Christopher Fowler, Umeå University, Sweden.

Antimuscarinic antiparkinsonian drugs

Antimuscarinic drugs can be useful in drug-induced parkinsonism. This family of drugs are generally not used in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease since they are less effective than dopaminergic drugs and are associated with cognitive impairment.

Orphenadrine, procyclidine and trihexyphenidyl (all administered as their hydrochloride salts) reduce the symptoms of parkinsonism induced by antipsychotic drugs. Procyclidine can be administered parenterally as an emergency treatment for drug-induced dystonia.

In idiopathic Parkinson’s disease, antimuscarinic drugs reduce tremor and rigidity but have little effect on bradykinesia. They may be useful in reducing sialorrhoea (hypersalivation).

Antipsychotic drugs

Antipsychotic use is associated with significant side-effects, most notably movement disorders (tardive dyskinesia) and weight gain. It is unclear whether the atypical (second-generation) antipsychotics offer advantages over older, first generation antipsychotics. Drop-out and symptom relapse rates are similar for both classes of drugs.

Both generations of medication block receptors in the brain’s dopamine pathways, but atypical antipsychotics often act on serotonin receptors as well.

The atypical antipsychotics amisulpride, olanzapine, risperidone and clozapine may be more effective but are associated with greater side-effects. Atypical antipsychotics have a greater propensity for metabolic adverse effects, weighed against the significantly higher risk of tardive dyskinesia (which can be caused by long-term/high dose administration) and other extrapyramidal symptoms of typical antipsychotics. The higher dopamine D2 receptor affinity of the typical antipsychotics underlies these latter side-effects. Quetiapine and clozapine are considered the lowest risk agents for precipitating tardive dyskinesia. NICE recommends that the choice of antipsychotic should be an individual one, determined by consideration of the particular profiles of the individual drug and the patient’s preferences. Some patients do not respond fully or even partly to treatment.

Typical antipsychotics (first generation drugs, also known as neuroleptics)

Chlorpromazine was the first antipsychotic to be discovered. It is one of the most sedating of the typical antipsychotics and also causes antimuscarinic effects. May be prescribed for managing schizophrenia and other psychoses, mania, short-term adjunctive management of severe anxiety, intractable hiccup, relief of acute symptoms of psychoses and nausea and vomiting of terminal illness (where other drugs have failed or are not available). May be used in children for some behavioural problems. Side-effects include psychomotor agitation, excitement, and violent or dangerously impulsive behaviour.

Benperidol is approved in the UK (and other countries, not in the US) for use in the control of deviant antisocial sexual behaviour (hypersexual behaviour).

Flupentixol is less sedating than chlorpromazine, but with more Parkinson’s effects. It may have an antidepressant effect, but has also been associated with suicidal thoughts. Notable side-effects include sweating, itching and rashes.

Haloperidol is less sedating and causes fewer antimuscarinic side-effects than chlorpromazine, but more neuromuscular effects, especially muscle spasms and restlessness. Haloperidol is contra-indicated alongside fluoxetine (raises haloperidol levels), carbamazepine (lowers haloperidol levels) or lithium (increased risk of toxic effects).

Levomepromazine is more sedating than chlorpromazine, and poses a risk of causing hypotension, particularly in people over 50.

Pericyazine (periciazine) is more sedating than chlorpromazine, and poses a risk of causing hypotension when treatment starts. It is approved in the UK (and other countries, not in the US) for the management of schizophrenia or other psychoses, and as short-term adjunctive management of severe anxiety, psychomotor agitation, and violent or dangerously impulsive behaviour. Contact skin rashes from handling the tablets may occur.

Perphenazine is less sedating than chlorpromazine, but causes more neuromuscular side-effects, especially muscle spasms, particularly at high doses. It may cause blurred vision.

Pimozide is less sedating than chlorpromazine. It may cause depression. Nocturia is common. Because high doses can cause serious disturbances in heart rhythm, avoid prescribing with other antipsychotics, tricyclic antidepressants, and other drugs which affect the heart. Warn patients to avoid grapefruit juice whilst taking this medication.

Prochlorperazine is less sedating than chlorpromazine, but causes more neuromuscular side-effects, particularly muscle spasms. Contact skin rash may occur from handling tablets.

Promazine is as sedating as chlorpromazine. Contact skin rash may occur from handling tablets.

Sulpiride is less sedating than chlorpromazine and has a different chemotype. Skin pigmentation, and sensitivity to sun are common side-effects. Contact skin rash may occur from handling tablets.

Trifluoperazine is less sedating than chlorpromazine, and is less likely to lower body temperature or blood pressure, and causes fewer antimuscarinic effects than chlorpromazine. Produces neuromuscular side-effects, and restlessness, especially when the dose is over 6mg/day, and it may cause agitation. Trifluoperazine may cause spontaneous ejaculation.

Zuclopenthixol is as sedating as chlorpromazine. It may cause tinnitus, vertigo, drooling and thirst.

Atypical antipsychotics (second generation drugs)

Most of these drugs may be prescribed for the management of schizophrenia, and some of them are also licensed for mania. They may also be used for psychotic episodes in severe depression.

Risperidone and olanzapine in particular should not be used to treat behavioural problems in older dementia patients because of evidence showing that these drugs significantly increase the risk of stroke in these group. The most significant side-effects of atypical antipsychotics are weight gain and associated metabolic effects. Other important side-effects include somnolence, dizziness, neuromuscular symptoms, postural hypotension, which may be associated with fainting or tachycardia in some patients.

Amisulpride can be prescribed to control both positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Parkinsonism is a very common side-effect. Insomnia, anxiety, agitation, raised prolactin levels causing milk production, and associated sexual problems are also recognised side-effects. Amisulpride should be prescribed with caution in patients with kidney problems and in older patients. It should not be used in pregnancy or while breastfeeding.

Aripiprazole does not cause as much weight gain as some of the other atypical antipsychotic drugs. Side-effects commonly include Parkinsonism and sialorrhea. Light-headedness, insomnia, nausea and vomiting, indigestion, headache and lack of energy may also be experienced. Aripiprazole should be prescribed with caution in people with a history of seizures and should not be taken during pregnancy or while breastfeeding. Aripiprazole may take days or weeks to have its full antipsychotic effect. Warn patients to avoid grapefruit juice whilst taking this medication. Aripiprazole interacts with carbamazepine in such a way that the dose of aripiprazole should be doubled if they are given together.

Asenapine is prescribed for managing manic episodes in bipolar disorder, and not for other psychoses. Common side-effects include anxiety and drowsiness as well as weight gain and increased appetite, muscle spasms, extreme restlessness, Parkinsonism, and involuntary movements, dizziness, unusual taste sensations, numb lips and mouth, raised liver enzymes, stiff muscles and fatigue. Asenapine should not be prescribed to patients with severe liver insufficiency, and it is not suitable for patients with dementia.

Clozapine may be prescribed for managing schizophrenia when other antipsychotics are ineffective or unsuitable. Because of the severity of the possible side-effects, the prescribing psychiatrist, the patient and the supplying pharmacist must all be registered with the appropriate Patient Monitoring Service/access system. Side-effects include sedation, sialorrhea, tachycardia, blood pressure changes (high or low), dizziness, headache, and dry mouth. Some of these improve, although tachycardia, sialorrhea and sedation may persist.

Olanzapine may be prescribed for managing schizophrenia, mania (in combination with mood stabilisers) and preventing recurrence in bipolar disorder. Side-effects include Parkinsonism, and metabolic syndrome and weight gain is often very marked. Olanzapine should not be prescribed for dementia patients. It should be used with caution in pregnancy, in men with prostate problems, and in patiebts with paralytic ileus, or liver or kidney problems, or those taking certain types of heart drugs. Carbamazepine lowers the circulating level of olanzapine.

Paliperidone is the active metabolite of risperidone. It therefore shares most of risperidone’s characteristics. A prolonged-release formulation is available which releases steadily over a 24-hour period, stabilising the level of the drug in the blood. The most common side-effect is headache. The usual side effects of antipsychotics may occur, including Parkinsonism, and other neuromuscular effects, raised prolactin with sexual effects and effects on heart rhythm.

Quetiapine may be prescribed for managing schizophrenia and for manic episodes, either alone or with mood stabilisers. It is especially useful when treating patients with intolerable Parkinson’s symptoms, or symptoms of raised prolactin levels caused by other drugs. Side-effects are similar to those caused by clozapine, but quetiapine is not associated with serious blood disorders. It causes fewer neuromuscular side-effects than the older antipsychotics.

Risperidone may be prescribed for managing psychotic illnesses and for mania. It is thought to improve both positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. It has side-effects similar to chlorpromazine, but neuromuscular side-effects are usually less marked. However, it is more likely to cause Parkinsonism than most other atypical antipsychotics. Insomnia, agitation, anxiety, headache, weight gain, and nocturnal enuresis are common side-effects. Risperidone should not be prescribed for dementia patients. It should be used with caution in patients with liver or kidney disease, epilepsy or heart disease, as hypotension can occur. It may aggravate Parkinson’s disease. Carbamazepine lowers serum risperidone levels.

Depot injection antipsychotics

Some antipsychotics are available in slow-release formulations, administered by intramuscular injection. Injections are given between once/week and once/month depending on response, severity of condition and drug preparation prescribed.

Typical antipsychotics available in these formulations tend to contain nut oils, and are therefore unsuitable for use in patients with nut allergies.

Depot injections of older antipsychotics may cause more neuromuscular reactions than oral drugs, for example depot flupentixol decanoate causes more neuromuscular side-effects than chlorpromazine (and contains nut oil). Depot zuclopenthixol decanoate may be more suitable for patients who are highly agitated, while flupenthixol decanoate may be more suitable for patients with low mood associated with their condition.

None of the slow-release formulations of depot atypical antipsychotics contain nut oils. Atypical antipsychotics available in slow-release formulations include:

- olanzapine embonate

- paliperidone palmitate

- aripiprazole

- risperidone

RESOURCES

This lecture presented by Favio Guzman (Pharmacology Instructor, University of Mendoza, Argentina) provides a 6 minute overview of the terminology used and pharmacology of the typical and atypical antipsychotics.

Dementia drugs

Acetylcholinesterase inhibiting drugs such as donepezil, galantamine and rivastigmine are used in the treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Rivastigmine is also licensed for mild to moderate dementia associated with Parkinson’s disease. Efficacy relates to the cognitive enhancing action of these drugs. Benefit is assessed by cognitive assessment after around 3 months of treatment and treatment should be discontinued in those thought not to be responding. If further cognitive deterioration is measurable 4 to 6 weeks after discontinuation, consideration should be given to restarting therapy. Memantine, a non-competitive NMDA (glutamate) receptor antagonist, can be used for moderate Alzheimer’s disease in patients who are unable to take acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, and for patients with severe disease.

Drugs used to manage schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a disorder of the mind that is debilitating and chronic. The prevalence of this disorder is about 1% of the population and seems to affect all areas of the globe equally. It is not well understood what causes the disorder. Some combination of genetic and environmental factors contributes toward the development of this disease, which is characterized by an alteration of brain structure and chemistry mainly involved in dopamine and glutamate pathways.

Symptoms include hallucinations, delusions and disorganized thoughts and behaviors that cause an individual to withdraw socially and exhibit psychosis such that they are unable to differentiate the hallucinations and delusions from reality. As with most diseases, schizophrenia can range in severity. Some individuals exhibit mild symptoms and are able to live relatively normal lives while others exhibit severe symptoms requiring hospitalization and specialized care.

Symptom onset typically begins in early adulthood. Diagnosis is made based upon the symptoms exhibited instead of on lab tests. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) lists the criteria by which a schizophrenia diagnosis is made. DSM-5 lists both positive and negative symptoms of the disease, which are included below.

Positive Symptoms

- Hallucinations – sensing things that are not real (hearing voices, seeing things)

- Delusions – believing things that are not real (the doctor is poisoning me through my medications)

- Disorganized thoughts/behaviors – incoherent speech, purposeless behavior, difficulty communicating thoughts (jumbling words together meaninglessly or stopping in the middle of a sentence)

Negative Symptoms

- Loss of interest in everyday activities

- Lack of emotion

- Poor hygiene

- Social withdrawal

- Loss of motivation

- Lack of speech

Schizophrenia is believed to be a disorder involving abnormalities in brain chemistry. Patients with schizophrenia have elevated dopamine levels within certain parts of their brain and also altered glutamate levels. The role of glutamate is not well understood, so treatment primarily involves blockade of dopamine receptors. Newer agents also block other receptors including serotonin, but as the pathophysiology of the disease is not fully understood, it is unclear how alteration of other neurotransmitter pathways exert therapeutic effects. Drugs are effective at treating positive symptoms of the disorder, but often are poor at treating the negative symptoms. If negative symptoms do respond to treatment, they typically take longer to correct compared with positive symptoms.

First Generation Antipsychotics (FGAs) such as chlorpromazine, thioridazine, perphenazine, thiothixene, and haloperidol work primarily by blocking dopamine (D2) receptors and also block serotonin (5-Hydroxytryptamine) receptors in the brain to a lesser extent. Most first generation antipsychotics carry a risk of extra-pyramidal symptoms (EPS), sedation, orthostatic hypotension, tachycardia and anticholinergic effects. Other side effects include weight gain and sexual dysfunction. In addition, thioridazine and haloperidol carry risks of QT prolongation.

Second Generation Antipsychotics (SGAs) such as clozapine and aripiprazole work by blocking D2 and serotonin receptors; however, some agents have additional mechanisms of action. Aripiprazole, brexpiprazole and cariprazine are D2 and serotonin 5-HT1A receptor partial agonists. Brexpiprazole also acts as a serotonin 5-HT2A antagonist. SGAs have multiple unwanted effects including metabolic side effects (hyperglycemia, weight gain and lipid abnormalities) and increased prolactin levels (risperidone and paliperidone) causing gynecomastia, irregular menstrual cycles, and sexual dysfunction. QT prolongation is a concern with ziprasidone, quetiapine and risperidone. Clozapine is one of the most effective agents for treatment resistant schizophrenia, but carries a host of black box warnings for seizures, agranulocytosis, myocarditis and metabolic abnormalities. As a result of clozapine’s side effects, absolute neutrophil count and white blood cell count must be monitored at baseline before initiation of the medication, periodically thereafter as long as the patient remains on therapy, and for 4 weeks after therapy is discontinued. SGAs typically have a lower risk of EPS compared to FGAs, but they can still occur, especially at higher doses.

Some antipsychotic agents carry an increased risk of cerebrovascular effects (e.g. stroke) when used to treat dementia-related psychosis in elderly patients.

Schizophrenia/psychosis is a concern in patients with Parkinson’s disease because agents used to treat Parkinson’s disease typically increase dopamine levels. Almost half of patients with Parkinson’s disease will experience hallucinations or delusions at some point during their treatment. Treating psychosis in these patients can be difficult because antipsychotics that antagonize dopamine receptors can worsen movement disorders in these patients. As a result, quetiapine is typically used because it carries the least risk of EPS among all antipsychotics. Additionally, pimavanserin can be used in this patient population because it treats psychosis by altering serotonin levels and does not affect dopamine levels, minimizing the risk of EPS and disrupting Parkinson therapy.

Medication adherence is poor among schizophrenia patients. Delusions can lead these patients to believe that the medication prescribed is actually poison; medication side effects can be difficult to tolerate, and disorganized thought patterns can lead to the belief that the medication is unnecessary, causing patients to stop taking prescribed therapies. To aid with adherence, some medications are available in formulations aimed to improve medication adherence. Long acting depot injections are popular and are available for several FGAs and SGAs; effects last between 2 weeks and 3 months per injection. Also, orally disintegrating tablets are popular methods in improving adherence; these tablets dissolve as soon as they reach the mouth and prevent “cheeking” of medications (storing medication in the cheeks and spitting out when medical professionals exit the room).

Finally, antipsychotics, especially FGAs, cause a variety of EPS ranging from akathisia (restless movements of extremities accompanied by anxiety), parkinsonism and tardive dyskinesias (TD). Akathisia is treated utilizing central anticholinergics such as diphenhydramine. It can also be treated with propranolol. Parkinsonism looks like Parkinson’s disease with tremors, rigidity and abnormal gait. It is caused by imbalance of dopamine levels in the basal ganglia and can be treated with central-acting anticholinergics, and more importantly the fine titration of the antipsychotic drugs. TD involves abnormal involuntary movements of the tongue, lips, face, trunk or eyes. If TD develops, the FGA must be discontinued and replaced with an SGA with low EPS risk such as quetiapine or clozapine. TD can be irreversible and the risk of it becoming irreversible affects the duration of the treatment.

Contributors: Daniel Paul, Kelly Karpa

RESOURCES

This is a 6-minute narrated, animated video describing the treatment of schizophrenia, including first and second generation antipsychotics. It is suitable for beginners.

Produced by the Khan Academy.

This summary, created by the National Institute of Mental Health, provides a written overview of schizophrenia, detailing its signs and symptoms, risk factors and treatments. It is suitable for beginners.

Hypnotic and anxiolytic drugs

The pharmacology of drugs with anxiolytic, sedative, and hypnotic effects overlaps significantly, with different doses of the same drug having effects ranging from sedation to loss of consciousness. So it can be difficult to ascribe just one function to each drug. The job of the prescriber is to identify the drug which offers the best therapeutic outcome for their patient.

Benzodiazepine class drugs are the most commonly used anxiolytics and hypnotics. They act selectively on gamma-aminobutyric acid-A (GABAA) receptors in the brain. Benzodiazepines enhance response to the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA, by opening GABA-activated chloride channels, thereby rendering neurons resistant to excitation. Benzodiazepine family drugs are similar in pharmacological action but vary in potency and clinical efficacy in treatment of particular conditions. Benzodiazepines are used as sedatives, hypnotics, anxiolytics, anticonvulsants and muscle relaxants.

In clinical practice, benzodiazepines are indicated only for short-term relief (two to four weeks) of severe, disabling or distressing anxiety.

Note that:

- It is considered inappropriate to prescribe benzodiazepines for short-term ‘mild’ anxiety.

- Benzodiazepine use to treat insomnia should only be considered when the insomnia is severe, disabling, or is causing extreme distress.

Hypnotics prescribed for insomnia

Benzodiazepine hypnotics

Benzodiazepines used as hypnotics include the long-acting drugs nitrazepam and flurazepam. However, these may cause residual effects the following day and repeated doses are cumulative.

Loprazolam, lormetazepam, and temazepam are shorter acting drugs with little or no hangover effect. Unfortunately, the short-acting benzodiazepines are more commonly associated with withdrawal symptoms. Short-acting hypnotics are preferable in patients with sleep onset insomnia, when hangover sedation is undesirable.

In patients whose insomnia is associated with daytime anxiety, use of a long-acting benzodiazepine anxiolytic such as diazepam given as a single dose at night may effectively treat both symptoms.

Note that:

- Chronic insomnia rarely benefits from hypnotic administration.

- Routine prescribing is undesirable, and use should be reserved for short-term acutely distressed patients.

- Prescribing of hypnotics to children, except for use in rare patients suffering night terrors and somnambulism, is not justified.

- Benzodiazepines and the Z–drugs (see below) should be avoided in the elderly, because they are at greater risk of becoming ataxic and confused, potentially leading to increased falls and injury.

Non-benzodiazepine hypnotics

Z-drugs: zaleplon (very short-acting), zolpidem tartrate and zopiclone (both short-acting drugs) are non-benzodiazepine hypnotics, which bind to a different site on GABAA receptors compared to the benzodiazepines, although they produce the same receptor activation. Dependence has been reported in a small number of patients. In the UK, NICE guidance recommends that Z-drugs use be restricted to the short-term management of severe insomnia that interferes with normal daily life, and should be prescribed for the shortest period of time possible. These drugs are not licensed for long-term use.

Buspirone hydrochloride is thought to act at serotonin 5-HT1A receptors. Response to treatment may take up to 2 weeks. The dependence and abuse potential of buspirone hydrochloride is low. Although it is licensed only for short-term use, specialists occasionally use it for several months.

The use of chloral hydrate and derivatives as hypnotics is now very limited, mainly due to the lack of evidence supporting clinical efficacy.

Clomethiazole may be a useful hypnotic for elderly patients because of its freedom from hangover effects, but as with all hypnotics, routine administration is undesirable and dependence occurs.

Some antihistamines such as promethazine hydrochloride and diphenhydramine are available over-the-counter for managing occasional insomnia.

The pineal hormone melatonin is licensed for the short-term treatment of insomnia in adults over 55 years.

Barbiturates

Barbiturates are a group of drugs derived from barbituric acid. They suppress central nervous system activity and are effective anxiolytics, antiepileptics, sedatives and hypnotics. Barbiturates act as positive allosteric modulators of GABAA receptors to enhance the action of neuroinhibitory GABA. They are classified according to their duration of action; short-, medium- or long-acting. As they have the tendency to cause tolerance and psychological and physical dependence, they are now rarely used as anxiolytics. Barbiturates are currently used principally for their hypnotic actions (in anaesthesia) and in rare cases as antiepileptics. The use of barbiturates as sedatives has been superceded by safer and more effective benzodiazepine drugs in routine clinical practice.

The intermediate-acting barbiturates amobarbital sodium, butabarbital (butobarbital), and secobarbital should only be used for the treatment of severe intractable insomnia in patients already taking barbiturates. Their use should be avoided in the elderly.

The long-acting barbiturate phenobarbital is still sometimes of value in epilepsy but its use as a sedative is unjustified.

The very short-acting barbiturate thiopental sodium is used in anaesthesia.

Older non-benzodiazepine drugs such as meprobamate and the barbiturates are not recommended as hypnotics as they have more side-effects and interactions (especially with alcohol) than benzodiazepines and are much more dangerous in overdose.

Levodopa

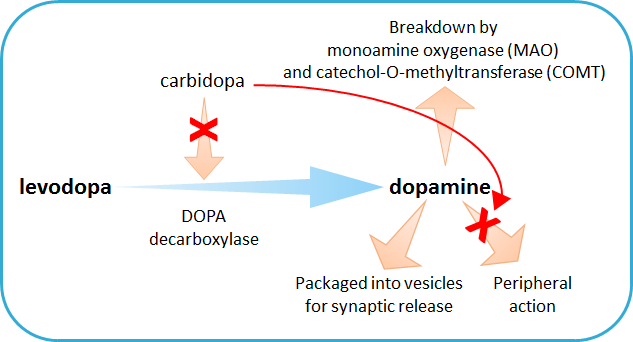

Levodopa (L-DOPA) is the amino-acid precursor of the neurotransmitter dopamine, used in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Administration of levodopa aims to restore dopamine levels which are significantly reduced in Parkinson’s patients. Levodopa has the advantage over dopamine that it can cross the blood-brain barrier, whereas dopamine cannot. Many of the adverse side effects (such as motor complications) seen with use of levodopa on its own arise from peripheral conversion to dopamine. To circumvent this, co-administration of peripheral DOPA decarboxylase inhibitors (DDCI) such as carbidopa (co-careldopa) or benserazide (co-beneldopa) is beneficial, and allow effective brain-dopamine concentration to be achieved with lower doses of levodopa (see image below). End-of-dose deterioration can be somewhat mitigated by using modified-release preparations, which can help reduce nocturnal immobility and rigidity resulting from drug effects wearing off.

Mood stabilising drugs

A variety of chemotypes are grouped together as the mood stabilising drugs, used in the management of bipolar disorder (manic depression), mania and hypomania, and sometimes recurrent severe depression. Naming these drugs as mood stabilisers belies their action of stabilising mood in patients who experience problems with extreme highs, extreme lows, or mood swings between extreme highs and lows.

Mood stabilisers should only be prescribed by mental health professionals, such as psychiatrists.

Lithium (Li+) is a natural inorganic substance, administered as carbonate or citrate salts. In addition to being used to manage bipolar disorder, lithium can also be used to manage recurring depression, schizoaffective disorder, self-harm and some aggressive behaviours. Blood lithium levels must be monitored regularly to maintain safe levels (<1.5mmol/l), and dose must be titrated for individual patients. One advantage that lithium has over other mood stabilising drugs is that it does not cause sleepiness or drowsiness. Patients should ask for advice from their health care professional before taking any non-prescription medicines alongside lithium, as some of these medicines (e.g. ibuprofen) can alter the body’s ability to excrete lithium, or alter fluid balance (as can some herbal and other complementary medicines) which indirectly alters blood lithium levels. The most common side-effects are thirst, nausea, dizziness, mild diarrhoea, and a metallic taste in the mouth, and taking lithium may cause weight gain. Signs of lithium overdose include loss of coordination, heavy tremors, muscle stiffness, difficulty speaking, confusion and in severe cases results in stupor, coma and even death.

Carbamazepine, lamotrigine and valproate (valproic acid) were originally used as antiepileptic medications, but are primarily now used as mood stabilisers. The molecular mechanisms of action of these drugs are poorly defined, but are suggested to involve inhibition of sodium and/or calcium channels.

Carbamazepine is used to manage bipolar disorder. It is not suitable for treating recurrent depression or acute mania. As with lithium, regular blood test should be used to monitor for safe and effective therapeutic levels. Taking carbamazepine alongside SSRI (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor) and tricyclic antidepressants can make the antidepressants less effective. Monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) antidepressants can increase carbamazepine to dangerous levels, so medical advice is to wait for 2 weeks after coming off MAOIs before beginning carbamazepine therapy. Carbamazepine can make oral contraceptives less effective, so alternative methods of contraception should be considered. Common side-effects include dizziness, tiredness, nausea, vomiting, skin reactions, increased susceptibility to infection (related to reduced white blood cell counts), dry mouth, headaches, blurred/double vision and weight gain.

Lamotrigine is prescribed for managing depression in bipolar disorder. An initial low dose should be trialled and increased if necessary, to reduce the likelihood of developing serious skin reactions, which is the most common lamotrigine side-effect. Other common side-effects include headaches, dry mouth, irritability, sleepiness, dizziness, nausea and vomiting. Carbamazepine can lower blood levels of lamotrigine, so the lamotrigine is likely to be less effective. Oral contraceptive pills can affect lamotrigine metabolism, so dosage modifications or alternative methods of contraception should be considered.

Valproate is prescribed for managing mania in bipolar disorder. Valproate is not usually suitable for recurrent depression. Common side-effects include nausea, vomiting, tremor, unsteadiness, loss of appetite and fluid retention. Valproate interacts with many other mood stabilisers and antidepressants. It increases levels of lamotrigine and carbamazepine, and levels of MAOI and tricyclic antidepressants, increasing the risk of unpleasant side-effects. Taking valproate with the antipsychotic, olanzapine can increase the likelihood of experiencing liver problems, weight gain and low white blood cell counts.

Asenapine is an atypical antipsychotic drug, but its main use is as a mood stabiliser. Its primary molecular action is as a serotonin and dopamine receptor antagonist, in particular antagonism of the dopamine D2 and serotonin 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors. This multireceptor mechanism helps to normalise the activity of the brain, reducing manic symptoms. Asenapine is prescribed for managing mania in bipolar disorder. Common side-effects are extreme sleepiness and anxiety. Asenapine can increase circulating levels of the SSRI antidepressant, paroxetine, which increases the risk of unpleasant side effects.

Opioid analgesics

Many opiod analgesics are available to the prescriber. Examples include morphine, diamorphine, codeine, dihydrocodeine, tramadol, oxycodone, meptazinol, buprenorphine, pentazocine, alfentanil, pethidine, remifentanil, papeveretum (a mixture of morphine hydrochloride, papaverine hydrochloride, and codeine hydrochloride [253:23:20], a.k.a. Omnopon), hydromorphone, fentanyl, and dipipanone. Pholcodine is sold OTC in the UK as an antitussive, it has very little analgesic action.

Codeine and dihydrocodeine are available in fixed-dose formulations with paracetamol (co–codamol and co–dydramol respectively), as is tramadol. The paracetamol appears to potentiate the opioid effects.

Some opioids are combined with anti-emetic drugs, for example with cyclizine (as in dipipanone plus cyclizine) or buclizine (as in Migraleve, with codeine and paracetamol) or hyoscine (plus papeveretum, a premedication mixture).

Common side-effects include opioid-induced constipation (OIC), dizziness, drowsiness, respiratory depression (at larger doses) and often nausea and vomiting in initial stages of treatment. Drowsiness may affect driving and performance of skilled tasks, so patients should be advised not to drive at the start of opioid analgesic therapy, or following dose increases. Patients should also be warned that effects of alcohol are enhanced whilst taking these types of drugs. Repeated use of opioid analgesics is associated with the development of psychological and physical dependence. Although this is rarely a problem with therapeutic use, caution is advised if prescribing for patients with a history of drug dependence. Naloxone is a specific antidote for the reversal of opioid induced CNS and/or respiratory depression as experienced either postoperatively or as a result of opioid overdose.

All opioids are contra-indicated in patients with acute respiratory depression, in comatose patients, patients with head injury or raised intracranial pressure (because opioid analgesics interfere with pupillary responses vital for neurological assessment), and patients at risk of paralytic ileus.

In the control of pain in palliative care the cautions associated with opioid use should not necessarily be a deterrent to their use.

Morphine derivatives are common recreational drugs causing dependence. FIxed-dose formulations of opioids plus naloxone can be used as adjunct in the treatment of opioid dependence, in particular for patients for whom methadone is not suitable; for example buprenorphine plus naloxone (Suboxone).

RESOURCES

This 12-slide slide set created with PowerPoint presents an introduction into the pharmacology of opioid analgesics in order to provide a basic background to facilitate later understanding of more detailed pharmacology of opioid analgesics. Topics covered include: opioid receptors, their signaling mechanisms and responses; and pharmacological effects of opioid receptor ligands. This introduction to the topic of opioid analgesics would be appropriate for intermediate level learners. Contributed by Christopher Fowler, Umeå University, Sweden.

This set of 17 slides introduces students (beginner to intermediate learners) to some of the basic physiological processes that are the targets of many analgesic drug classes. Specific areas covered include the regulation of nociceptive input to the spinal cord by processes within the superficial layers of the cord itself and also descending fibres from the brainstem. Drug classes are considered according to the World Health Organisation (WHO) classification of analgesics which include: (1) simple analgesics, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs), (2) weak opioid drugs (e.g. codeine), and (3) the most powerful opioids (e.g. morphine and its semi-synthetic derivatives). Drugs that do not align with the WHO classification, but which are used in neuropathic pain, are also mentioned in outline. Provided by Prof. JA Peters, University of Dundee School of Medicine.

Other antiparkinsonian drugs

Dopamine-receptor agonists

e.g. pramipexole, ropinirole, and rotigotine. Dopamine-receptor agonist monotherapy causes fewer motor complications in long-term treatment compared with levodopa treatment, however, the improvement in overall motor performance is not as good. Dopamine-receptor agonists can be administerd as adjunct to co-beneldopa or co-careldopa to reduce ‘end of dose’ deterioration. Dopamine-receptor agonists plus levodopa can be prescribed for more advanced disease, but the levodopa dose must be reduced.

Subcutaneous injection of apomorphine hydrochloride is sometimes helpful in advanced disease, especially for patients experiencing unpredictable ‘off’ periods with levodopa treatment. Patients are able to self-administer the drug at the first sign of an ‘off’ episode. Use of other antiparkinsonian medications can sometimes be reduced once apomorphine treatment is established.

Monoamine-oxidase-B (MAOB) inhibitors

e.g. rasagiline and selegiline hydrochloride are irreversible MAOB inhibitors. Both of these drugs can be used alone and in combination with anti-Parkinsonian drugs. Early treatment with selegiline hydrochloride alone can delay the need for levodopa therapy. Rasagiline is useful in dealing with non-motor symptoms such as fatigue.

Paracetamol (acetaminophen) and other simple analgesics

Paracetamol (acetaminophen) is not classed as an NSAID because it lacks anti-inflammatory activity and only weakly inhibits COX isoenzymes. The analgesic effect of paracetamol may involve its metabolites (e.g. N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine, which is also responsible for hepatotoxicity in overdosage). TRPA1 (an excitatory cation-selective ion channel) has emerged as a recent, novel, target that is activated by such metabolites (Gentry et al., 2015), as has the capsaicin receptor TRPV1 (Eberhardt et al., 2017).

RESOURCES

This set of 17 slides introduces students (beginner to intermediate learners) to some of the basic physiological processes that are the targets of many analgesic drug classes. Specific areas covered include the regulation of nociceptive input to the spinal cord by processes within the superficial layers of the cord itself and also descending fibres from the brainstem. Drug classes are considered according to the World Health Organisation (WHO) classification of analgesics which include: (1) simple analgesics, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs), (2) weak opioid drugs (e.g. codeine), and (3) the most powerful opioids (e.g. morphine and its semi-synthetic derivatives). Drugs that do not align with the WHO classification, but which are used in neuropathic pain, are also mentioned in outline. Provided by Prof. JA Peters, University of Dundee School of Medicine.

This is an 18 slide presentation covering the physiology underlying nausea and vomiting, and the pharmacology of pro- and anti-emetic drugs. Provided by Prof. JA Peters, University of Dundee School of Medicine.